It would be extremely difficult — if not impossible — to predict what today’s students must know to fully prepare for the economy of the future. What we do know for certain is that having the capacity to communicate, collaborate, and problem-solve, among other so-called soft skills or employability skills, is essential for success no matter the industry.

School systems are ramping up efforts on this front in response to an increasingly thunderous cry from employers, who say they’re frustrated by the struggle to find new hires who show up on time, meet deadlines, and get along with others.

A tightening labor market makes the matter all the more urgent. As of January 2019, the number of U.S. job openings had reached a high of 7.3 million—and that number is expected to double over the next five years. Deloitte and the Manufacturing Institute’s 2018 Skills Gap Study showed that unfilled jobs over the next decade could cost the U.S. economy more than $2.5 trillion.

Paige Boetefuer, director of soft skill programming at YouthForce NOLA, teaches soft skills to students. (Photo credit: YouthForce NOLA)

The Test of Life

Not that school districts are solely responsible for what NSBA’s Commission to Close the Skills Gap calls “LifeReady Skills.” But they are in a prime position to impact today’s students — a generation accustomed to communicating through texts, emojis, and memes — long after they receive their diplomas.

Indiana thought so, too. Under a law passed by the state’s General Assembly, all schools as of July 1, 2019, are required to incorporate interdisciplinary employability skills.

“We put so much pressure on testing, and at the end of the day, none of these tests are going to necessarily get you that first job,” says Adam Dovico, who has been a teacher, principal, and clinical professor in North Carolina and Georgia. “But the test of life — having good interactive skills — is going to get you really far.”

When Dovico was principal at the K-5 Moore Magnet Elementary School in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, every classroom had a designated greeter. With every classroom visitor, the greeter — a rotating position to give everyone practice — would stand up, walk over, shake hands, and say, “Welcome to our class.”

He also helped organize the districtwide “Amazing Shake,” a competition he helped create in 2010 while working at the Ron Clark Academy in Atlanta—now a national competition for students in grades five through eight who are top performers when it comes to manners, discipline, respect, and professional conduct.

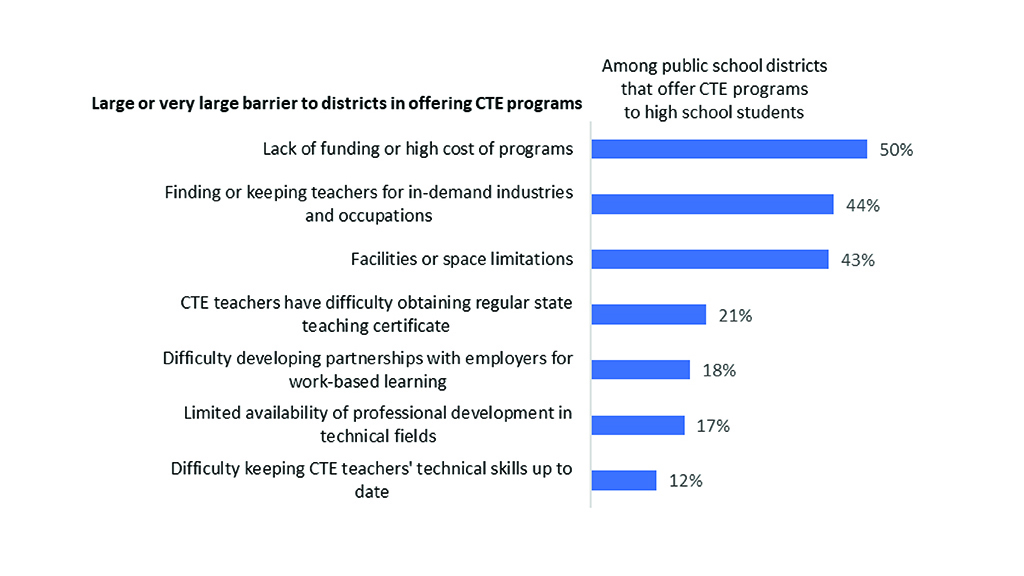

Main challenges that school districts face when offering CTE programs

Such interactions build confidence while teaching traits and behaviors important for finding success in school and beyond.

In a recent report, the Commission to Close the Skills Gap defined the following skills as most critical for young people to master in preparation for future opportunities: dependability and reliability, adaptability/trainability, critical thinking, decision-making, customer focus, and teamwork.

Career and technical education (CTE) programs — no longer considered solely an alternative to traditional education, as they increasingly intersect with core academic subjects — have been front and center in the soft skills debate. (And it is a debate. Some critics think the idea of a gap is overblown, and that employers need to change their hiring practices.) Many believe CTE programs are an excellent way to teach soft skills.

“The idea is to make cross-content connections and dispel the notion that CTE is a segmented area for certain students who don’t necessarily enjoy—or haven’t been successful in—the core academic setting,” says Eric Mastey, director of CTE at J. Sterling Morton High School District 201 in Cicero, Illinois.

Two students collaborate on developing soft skills during a training organized by YouthForce NOLA (Photo credit: YouthForce NOLA)

School-Workforce Partnerships

J. Sterling Morton High School District 201 is a ninth through 12th-grade district “that incorporates CTE everywhere, with intentionality,” explains Mastey. “Teachers work more as coaches or mentors, similar to a boss or supervisor in a place of business. You can’t simply teach students how to take responsibility, how to empathize, how to work with lifelong skills, or be assertive without being creative.”

To his point, within the district’s automotive program, staff¬ members are able to bring in their cars for service. By students’ third or fourth year in the program, they are expected to make a diagnosis, provide a written rate for service, converse with the customer, and either perform the service or communicate to peers about what service needs to be performed.

The school has a good relationship with the local labor unions, connecting students with mentors and apprenticeships. In addition, business owners involved with the school’s professional advisory committees get an inside look at classroom space and curriculum, and frequently offer students jobs—at above minimum wage—right out of high school.

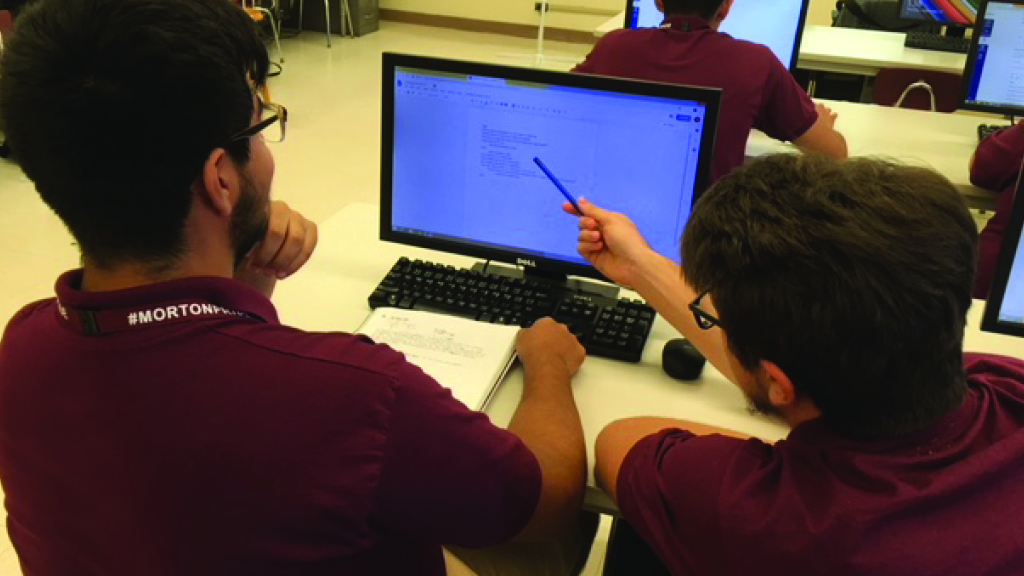

J. Sterling Morton High School District 201 computer science students work in teams to create, test, and troubleshoot algorithms for computer programs in the development stage. (Photo credit: J. Sterling Morton High School District 201)

Two years ago, The Hechinger Report, an independent education news organization, launched “The Map to the Middle Class,” a project exploring what it takes to ascend to the middle class in an evolving economy. Through its reporting, soft skills repeatedly came up in conversation. Employers pointed to them as being weak in job candidates. They translated across industries. And they likely will not be acquired by robots of the future.

Training often is most effective when schools partner with local industries to provide real-life workplace experiences, says The Hechinger Report senior editor Caroline Preston.

The report has highlighted innovative ways districts have done just that.

An internship program called Prepare Rhode Island, for instance, improves youth career readiness through a strategic partnership between the state government, private industry leaders, the public education system, universities, and nonprofits across the state.

“School officials are really strapped for time and resources, obviously, so getting assistance from local employers is a good way in,” says Preston. “Since school board members tend to be really well-connected to their community, they could play a role in brokering those relationships.”

J. Sterling Morton High School District 201 students use teamwork, communication, and customer service skills during a job shadow day. (Photo credit: J. Sterling Morton High School District 201)

Cate Swinburn sees the benefit of those relationships daily as president and co-founder of YouthForce NOLA. The education, business, and civic collaborative prepares New Orleans public school students to pursue high-wage, high-demand career pathways.

YouthForce NOLA got its start in 2015, with the goal of preparing students for local, high-wage job openings expected within the next decade.

When talking with employers about what makes candidates career ready, “soft skills came up again and again and again,” Swinburn says.

The collaborative provides soft skills training using a framework, developed by Chicago-based MHA Labs, of six building blocks: communication, collaboration, personal mindset, planning for success, social awareness, and problem-solving. For its career readiness and soft skills development program known as YouthForce Internship, students participate in 60 hours of soft skills training over the course of two weeks, followed by 90 hours of meaningful work experience in paid internships, with continued coaching and case management.

Meanwhile, an annual, yearlong Soft Skills Teacher Fellowship trains and supports educators to better integrate and execute soft skills into classroom curricula.

In partnership with more than 100 employers, YouthForce NOLA now works with 84 percent of Orleans Parish’s open enrollment public high schools and eight training provider partners, including community colleges.

Since its inception, the annual number of high school students earning industry credentials has expanded by 300 percent.

“To a certain extent, this is like opening a door and giving students capabilities they didn’t know were in their reach,” Swinburn says. “It’s both incredibly clarifying and magnificently empowering.”

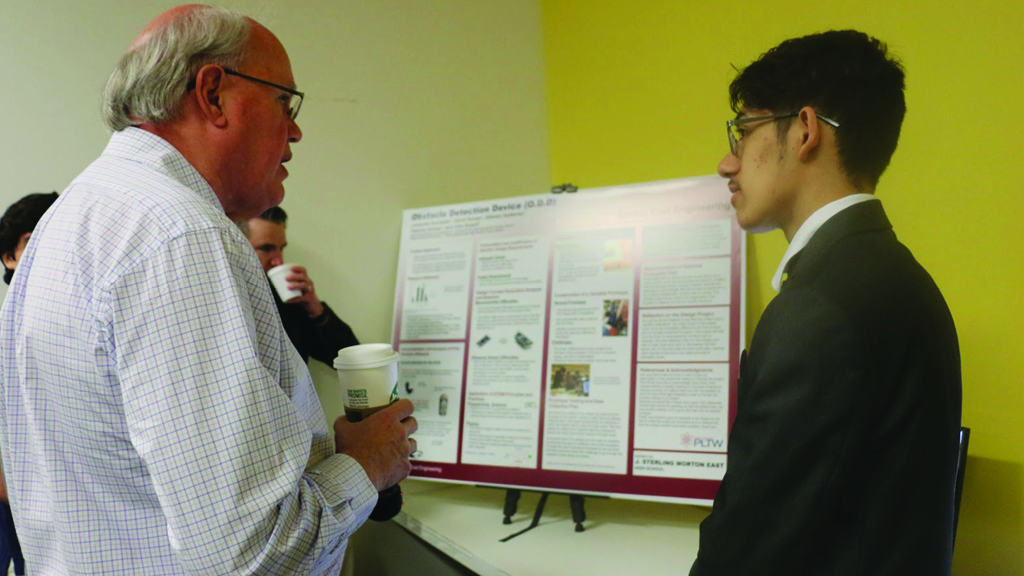

A J. Sterling Morton High School District 201 engineering student engages with an industry professional about his project and presentation at the Day of Innovation event. (Photo credit: J. Sterling Morton High School District 201)

Teaching Soft Skills Impacts Grades

The Karl G. Maeser Preparatory Academy in Lindon, Utah, began emphasizing soft skills with ninth-graders in 2007, but ultimately realized many students would benefit from learning them earlier, and therefore enter their freshman year better prepared. The public charter school serves 640 students in grades seven through 12.

Since 2010, every seventh-grader has been required to take a yearlong course from SOAR Learning Inc., a study skills curriculum in more than 4,000 schools and 40 countries worldwide. SOAR stands for set goals, organize, ask questions, and record progress. Students learn how to use a planner, organize papers, take notes, manage time, and communicate differently between peers and teachers, among other things.

Within one year of implementation, students had raised the schoolwide grade-point average by a full percentage point—a gain Director/Headmistress Robyn Ellis attributes to the course.

“This is not one of those throwaway classes, or an elective students can take if they want,” says Ellis. “The repetition and focus are extremely important and starting in middle school is pivotal.”

SOAR co-founder and President Brian Willer says the transition from elementary school to middle school, when students start to manage their own schedules, is the perfect time for this type of instruction.

“That’s a stressful situation for 12-year-olds,” he says. “More people need to take the time to formally teach them how to learn this stuff.”

'You Can't Workshop Someone Into Being Human'

Despite soft skills being notoriously difficult to measure, as of last school year, districts are able to do just that.

The nonprofit Project Lead The Way convened the world’s leading assessment experts—including those who have been involved with the Program for International Student Assessment and the National Assessment of Educational Progress—to create a new way to evaluate both soft skills and content knowledge.

The resulting end-of-course assessment, the first of its kind, measures mastery of skills such as problem-solving, critical and creative thinking, collaboration, communication, and ethical reasoning and mindset, as well as proficiency in computer science, engineering, and biomedical science. Approximately 575,000 high school students have taken the assessment, which uses simulations and scenarios to allow for more open-ended, strategic types of answers.

With a student’s permission, Project Lead The Way will share scores with universities and employers as early as freshman year.

President and CEO Vince Bertram anticipates other companies will join the market over time.

His advice to school boards: “Don’t assume any of these skills are taught in one class in our compartmentalized education system that often teaches things in isolation. These skills are not used in isolation. All classes should stress their importance and require students to apply them. Students need to see the connectivity.”

That’s exactly why teachers should be encouraged to incorporate soft skills training when opportunities arise, according to Leslie Beller, founder and CEO of MHA Labs, which provides CTE-embedded curriculum and educator training to nearly 60 schools and 200 programs in Chicago alone, in addition to districts in New York and Minnesota. The “MHA” in MHA Labs stands for “the means and measures of human achievement.”

Teachers “don’t have to adopt a comprehensive soft skills curriculum to make a difference, just key skill-building practices,” Beller says. It takes less than 30 seconds, for example, to tell a student working individually on a project, “I saw you stay focused for 45 minutes. That’s a fantastic example of your drive to get work done on time.” To someone else who didn’t get a project finished on time: “I’m acknowledging you were helping somebody else instead and I want to recognize your team-based work. Employers really value team players, so they are going to love working with you.”

“If you make a really good, thoughtful plan and give it time to develop and grow, this does work,” she says. “It’s not an intervention or a response to an intervention. Our tagline is ‘You can’t workshop someone into being human.’ You need to treat this as fundamental to the school experience.”

Dovico’s advice: “People expect soft skills to be for adults, and yes, to some degree they are, but starting to teach them late would be the equivalent of saying kids don’t need to start learning math until they have their first bank account. We need to start when they’re young so there’s not this sudden learning curve they have to take on.”

Robin L. Flanigan (robin@thekineticpen.com) is a freelance writer in Rochester, New York. Her mindfulness-themed ABC/ poetry book is forthcoming.

Share this content