May 25, 2021, was another discouraging day for educators and policymakers. The Nation’s Report Card, also known as the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP), released the 2019 science assessment results, and data show that science scores for fourth-grade students have declined from the 2015 peak, while scores for eighth- and 12th-grade students have remained flat over the last decade. Media outlets like Forbes commented, “Scores for low-performing students get steadily worse, and the explanations are muddled.”

Some education leaders believe that poor reading comprehension skills are culpable for students’ low performance in science. However, science education professor Cary Sneider ― a former member of the NAEP Governing Board ― pointed out that “too much focus on” reading and math was crowding out science on school schedules. He urged principals and school leaders to “mandate a minimum amount of time on science each day.”

Recent research shows that teachers who spent five hours or more each week on science were dramatically more likely to incorporate forms of inquiry-based learning, a pedagogical method that encourages hands-on and collaborative approaches like group activities and discussions of engineering problems. In addition to mandating time for teaching science and implementing certain science standards, there should be a link between school infrastructure and science pedagogy. It is pivotal to create a space for students to learn science, engage in science at their early age, and even pursue science lifelong.

School Infrastructure Matters in Science Education

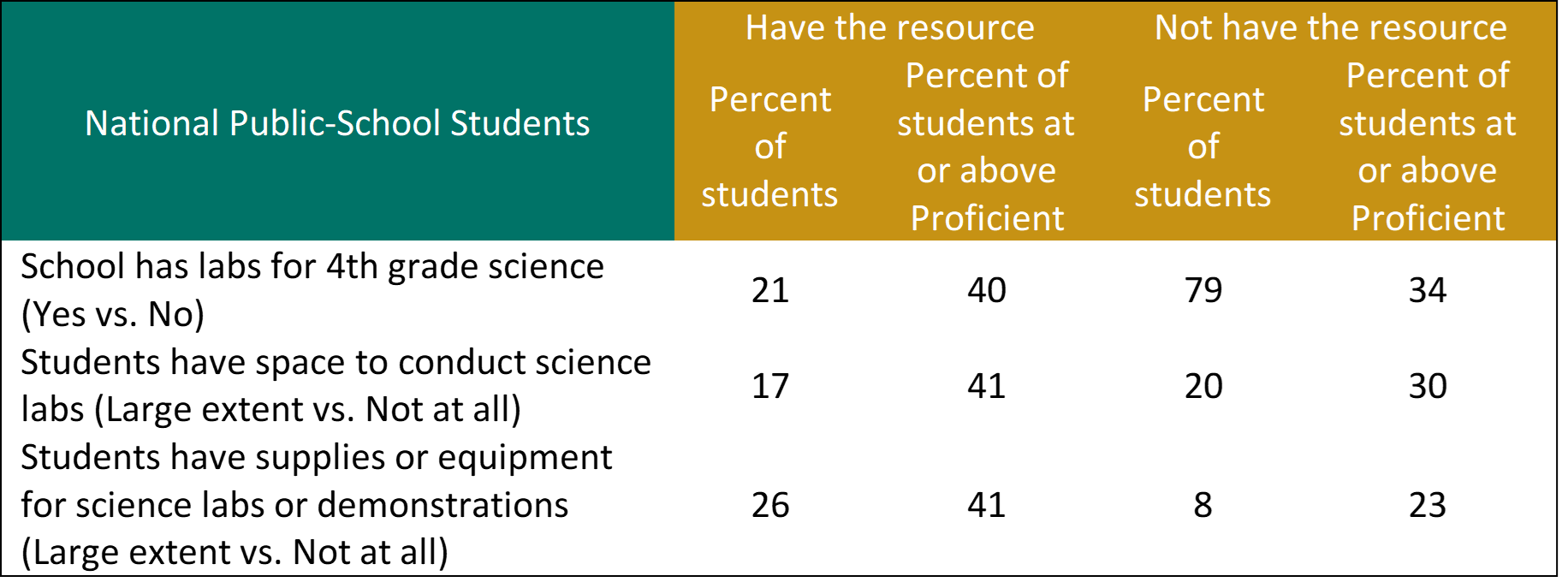

In the context of science education, school infrastructure may refer to science labs and other learning spaces for students to explore, experience, and conduct experiments for science projects. The 2019 NAEP data show that among the fourth graders in public schools, approximately 79% did not have labs for fourth-grade science, 20% did not have any space to conduct experiments during science classes, and 8% did not have any supplies or equipment for science labs or demonstrations (Table 1).

Table 1. Percentage of Fourth Graders and Percentage of Fourth Graders at or above Proficient, by Response to Infrastructure Resources: 2019 NAEP Science

Note: Some apparent differences in science scores between estimates may not be statistically significant. Source: NDE Core Web (nationsreportcard.gov)

The data clearly show that fourth graders who had large spaces to conduct science experiments and large supplies/equipment for science demonstrations performed better than their peers who did not have those infrastructure resources. Due to sample size issues, the estimated differences in student science scores may not be statistically significant between comparison groups. While the data have limitations, the trend is consistent with findings from research on the relationship between student achievement and access to resources or quality school infrastructure.

- Kapila and Iskander (2014) reported that a higher percentage of students who used the sensor-based labs (more than 60%) passed the Regents Living Environment exam than did students who did not use the lab (less than 40%). The modernized labs allowed students to interactively experience important science concepts, visualize what their EKG looks like, raise questions, and then investigate.

- Leithwood and Jantzi (2009) concluded that quality infrastructure in smaller schools contribute positively to student outcomes, including higher student achievement, better attendance, higher graduation rates, and greater engagement in extracurricular activities, particularly for disadvantaged students.

- Earthman (2004) pointed out that the link between basic school conditions and student achievement led to equity issues. His research has found that students in poor buildings scored 5-10 percentile rank points lower than students in functional buildings on academic tests after controlling for socioeconomic status.

Remake Learning, a Forward-Looking Philosophy for Science Education

Create, expand, and maximize learning spaces for students to have higher achievement. This goal has been ever present since the days of the one-room schoolhouse. According to Remake Learning ― a network of innovative and forward-looking educators and parents ― “from shared seats and long benches to individual desks, from blackboards to whiteboards to smartboards, learning spaces have evolved over time in response to a changing world and students’ changing needs.”

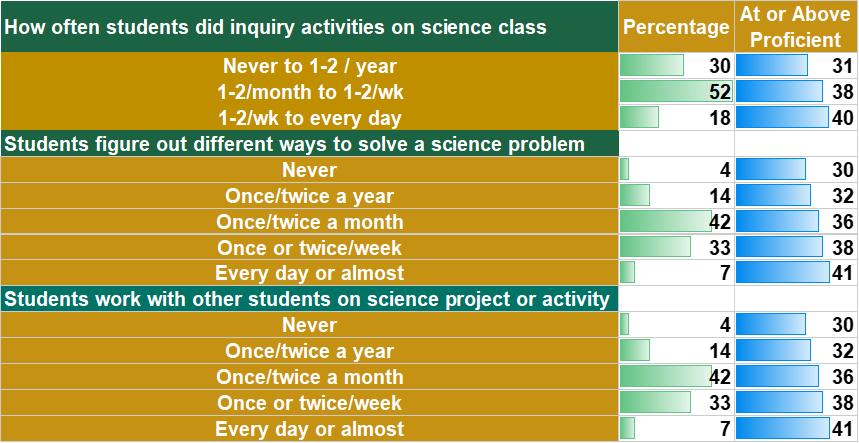

Schools should be safe and healthy and optimally designed to be conducive to learning, but how well students learn also depends on their interactions with their teachers mediated by the pedagogy being used. The 2019 NAEP science data suggest that high-performing students in public schools were more likely to frequently do inquiry activities on science classes, figure out different ways to solve a science problem, and work with their peers on a science project or activity (Table 2). Therefore, for best practices, school leaders may want to consider integration between creating physical learning spaces and innovating teaching methods.

Table 2. Percentage of Fourth-Graders and Percentage of Fourth-Graders at or Above Proficient, by Frequency of Using Certain Learning Methods: 2019 NAEP Science

Note: Some apparent differences in science scores between estimates may not be statistically significant. Source: NDE Core Web (nationsreportcard.gov)

“Even the smallest tweaks to the design of a learning space can add up to a change that fosters active participation and gets students to take ownership of their learning,” according to Remake Learning. Taking ownership of one’s learning is essential for science education, for science by nature is fun, and when students are filled with curiosity, learning takes place actively. The following are some examples from a Remake Learning booklet, which describe how innovative schools in the Pittsburgh area have transformed learning spaces to inspire students to investigate what they are curious to know and to do.

- The STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Math) Learning Labs at South Fayette Elementary School contain many technology tools that students need to learn, but the design of the space—bright paint colors to complement student work, flexible tables and chairs to allow for the right arrangement for each project, and tons of storage chosen specifically for the materials needed for STEAM learning—is central to the Labs being an effective learning space for students and teachers.

- At Montour Elementary School, only one thing — LEGO bricks ― outnumbers books at the library. The Brick Makerspace powered by LEGO Education is designed to give students room to move around, work together, and create anything they can imagine. Vehicle test tracks and engineering stations sit alongside low tables covered in Lego baseplates and equipped with plenty of places to store bricks.

- Seniors at Fox Chapel Area High School created a space for themselves, their peers, and learners all over their region to investigate and experiment. Students built a mobile fabrication lab on a flat trailer base. This red-roofed tiny house on wheels is a mobile makerspace that transports many of the same machines students used to build it—CNC machines, 3D printers, laser engravers, vinyl cutters, and more.

From Changing Learning Spaces to Changing Curriculum

The 2019 NAEP data show that, in public schools, fourth graders whose teachers reported team teaching science or teaching all subjects including science performed better than their peers whose teachers reported teaching science only or not teaching science. This information reinforces the idea that there are learning spaces where students can learn reading, math, and science altogether at the same time. Critical thinking and problem solving requires taking multiple areas of subject matter and creating solutions utilizing them all in tandem. Schools that employ project-based learning frequently develop a project or problem for students to solve or study combining multiple subjects.

The Elizabeth Forward School District (EFSD), a rural district in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, is a great example of how schools can be transformed from changing learning spaces to changing curriculum and how this transformation gets schools ready for the future. During the COVID-19 pandemic, EFSD was only closed for one day when switching from in-person schools due to closed buildings to full remote learning. According to the EFSD school leaders, transforming physical learning spaces became a key to the EFSD’s successful innovation.

The EFSD Superintendent, Dr. Todd Keruskin, described their initial motivation to change. About ten years ago, they saw students become bored in school and lose their interest in learning, and most important, they found schools were not preparing the skills that students needed in the future. They visited facilities equipped with innovative educational technology, such as the Entertainment Technology Center (ETC) of Carnegie Mellon University and the YOUmedia learning lab at the Chicago Public Library, and started changing spaces and programs one at a time over the last 10-12 years.

Gregg Behr of the Grable Foundation, the founder and co-chair of Remake Learning, said that the journey of Elizabeth Forward started with transforming one classroom in their high school, and with a small grant (about $10-12,000) awarded from the Grable Foundation, they physically redesigned the place. In that first year, a quarter of students in the high school enrolled in the class being offered in that classroom, simply because they wanted to be in that space, and two teachers even offered new types of elective courses.

The energy and enthusiasm of teachers and students embracing innovative learning spaces inspired the EFSD school leaders to seek more funding and more changes of learning spaces. However, EFSD did more than modernize classrooms and libraries. The district changed the learning landscape by involving educational technology and using interdisciplinary curriculum. For instance,

- For elementary students, an unused classroom was transformed into a 3D space where students could collaborate with their classmates and interact with software during a lesson. In the lab, students could explore science and learn vocabulary using their bodies instead of paper and pencils. “I learned about the content in class, but I didn't understand it until we worked on it in SMALLab as a group,” students often reported.

- In the High School Gaming Academy, students with different interests and talents ― artists, computer science students, and storytellers ― were brought together to build apps and games.

The EFSD leaders firmly believe that such types of programs create time, space, and opportunities to teach science by combining STEM with reading and arts, and give students the skills and creativity they will need to thrive in the new global digital workplace.

Conclusions

The debate on whether schools should spend more time on reading or on science seems off target. What is needed is to create environments where students can experiment, learn, and thrive, regardless of subject. As the Grable Foundation states, “From pre-kindergarten through twelfth grade, schools should ignite students’ interests, stretch their abilities, and set the path toward a future of possibility.”

Looking forward, educators and school leaders should see future demands, such as managing natural resources and living with artificial intelligence, and make decisions with strong grasp of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). As Remake Learning advocates, “Even young people who aren’t destined for careers in STEM fields will need to be STEM literate.” From the perspective of the science of learning, K-12 science education needs a forward-looking twist, namely creating teaching and learning spaces to inspire students to work collaboratively, act independently, think creatively, and use new technologies.

Share this content