PHOTO CREDIT: ALLISON SHELLEY FOR EDUIMAGES

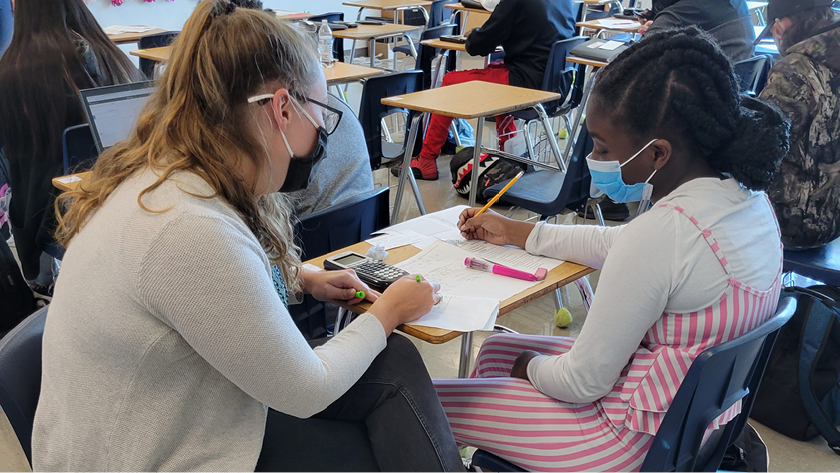

Call it learning acceleration or catching up on unfinished learning, the push is on to help students who are academically behind due to the impact of the pandemic.

State and national reports show that months of remote schooling stalled learning for many public school students. One analysis of assessments taken by more than 1.6 million elementary schoolchildren concluded that at the end of the 2020-21 school year, they were on average five months behind in mathematics and four months behind in reading. The pandemic “widened preexisting opportunity and achievement gaps, especially among historically disadvantaged students,” said the analysis by consulting firm McKinsey & Company.

In November 2020, when many of its students were still learning remotely, North Carolina’s Guilford County Schools launched an extensive one-on-one tutoring program. It targeted high school students who met multiple risk factors for not graduating, such as chronic absenteeism, course failure, underperformance on benchmark assessments, having a disability, and English learner status.

Graduate and undergraduate tutors from a local university were hired and trained to provide “high-dosage” tutoring to the students in math for two to six hours per week. Today, Guilford County’s initiative has expanded across grades and subjects and includes one-on-one and small-group instruction. It uses classroom teachers, college students, high school students, and volunteers from community partner organizations as tutors. Since the beginning of this school year, at least 5,600 tutoring hours have been logged, supporting 1,199 students, according to the district.

“We’ve been training tutors specifically for English learners, who seemed to be the hardest hit by this pandemic,” says Sharon Contreras, superintendent of the nearly 70,000-student district that includes Greensboro. Although a significant amount of work already has gone into the initiative, “We have a long way to go to make sure that all of our students are receiving the support that they need after nearly two years of being out of school,” she says.

EFFECTIVE STRATEGIES

Like Guilford County Schools, districts across the country are adopting a range of strategies and implementing program structures to get students on grade level.

In a fall review of 100 large and urban districts by the Center on Reinventing Public Education, 94 percent indicated plans to implement some learning acceleration strategies to catch students up on missed skills from previous years. Most identified extended learning (76 percent), followed by tutoring (62 percent), small-group instruction (45 percent), and using data to diagnose needs (41 percent).

“To solve unfinished learning, it’s critically important to understand where that unfinished learning may be happening,” says Kayla Patrick, a senior policy analyst with The Education Trust, an advocacy and research group focused on equity issues. “Some students may have had difficulty mastering certain math skills. Other students are having difficulty with literacy or other subject areas.”

Research briefs published in 2021 by Education Trust in partnership with MDRC, an education and social policy research organization, identified targeted intensive tutoring and expanded learning time as two evidence-based strategies shown to help students rebound from unfinished learning.

“What the research shows is accelerating learning as quickly as possible, instead of remediation, is the most impactful thing we can do,” Patrick says. “That doesn’t mean speeding through the content but filling in gaps where need be while continuing to introduce new content to students.”

INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORTS

Georgia’s Savannah-Chatham Public School System uses its emphasis on data-driven instruction to help identify students’ pandemic-related learning needs, says Bernadette Ball-Oliver, associate superintendent of secondary schools.

Along with the MAP (Measure of Academic Progress) assessment and i-Ready classroom assessments, the 37,000-student district’s EMBRACE Summer Learning program provided an additional resource for collecting data about students’ subject matter mastery, Ball-Oliver says. “That data allowed us to exactly see how we needed to meet the needs of students.”

One district innovation that came out of that data is the Twilight K-5 Virtual Learning option, which offers remote learning during nontraditional classroom hours for elementary students. The after-hours program helps accommodate the scheduling needs of families, whose children need additional support. It provides live, teacher-led instruction from 4:30 to 7:30 p.m., Monday through Friday. Students receive instruction aligned to the Georgia Standards of Excellence in English language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies, and they are taught by certified teachers. “We also integrated a little fine arts and physical education,” says Kaye Aikens, associate superintendent of elementary and K-8 schools.

Although not a tutoring initiative, the Twilight program, along with the recently launched Savannah-Chatham E-Learning Academy, and the academic review sessions offered during Saturday School programs (available in person and online) represent some of the institutional supports that the district has put in place to advance student learning, Ball-Oliver, says.

Many K-8 schools have created blocks of time in their schedules that are “strictly for targeting intervention,” says Julian Childers, superintendent of school transformation and innovation.

At the high school level, some schools have altered their master schedules to allow for extended learning in select classes. Instead of a one-semester Algebra 1 course, for example, the class may run the entire year, embedded with an academic support component to help students thoroughly master the content. “We call it a double dose,” Bell-Oliver says.

Strategies including instructional walkthroughs, in which instructional improvement specialists and leaders from academic affairs observe classroom teaching and provide advice to teachers and principals, along with weekly data meetings to assess students’ mastery of concepts, are also elements of Savannah-Chatham’s work to address unfinished learning, Aikens says.

Data is key to providing the meaningful feedback needed to reteach material that will improve student outcomes, she adds.

ACCELERATE LEARNING

Addison Davis, superintendent of Florida’s Hillsborough County Public Schools, recently mailed a card to every educator who has retired from the Tampa district in the last several years asking them to come back as interventionists and mentor coaches to work with students in need. The goal is a “full-court press to have everyone we can at the table, to create a longer, stronger bench to help our students,” Davis says.

In its effort to expand support to students of all abilities and all economic backgrounds, Hillsborough County Schools began partnering with the virtual tutoring platform Paper in the fall. With 24/7 access to tutors and multilingual options across 200 content areas, the service fits the 220,000-student district’s need to “reimagine the way we provide ongoing opportunities to accelerate learning,” Davis says.

All tutoring sessions are recorded, so those interactions can be used by teachers and school leaders to address learning weaknesses and inform classroom instructions, Davis says. “This also gives district administrators a better idea of what ongoing professional development needs to happen so we can build the capacity of our staff.”

While Hillsborough County Schools makes Paper available to district students in grades six to 12, it provides students in grades preK through five with virtual access to a team of certified teachers hired to provide support and “move the needle instructionally.” The Virtual Support Teachers resource was initially launched to assist students quarantined due to COVID-19 status. But students out of school for other reasons also use the service.

Hillsborough did not extend additional hours to the school day districtwide, but it did provide financial support to each individual school to extend the learning day, “be it before or after school for students who may need additional assistance,” Davis adds. Some are using the funds to offer “very intentionally focused Saturday learning” to solidify skills.

Across the board, the district has focused on an “accelerated learning approach” in which “we have stacked standards within each other” to expose students to important content that needs to be targeted, Davis explains. As part of that effort, instructional guides were “redefined to eliminate remediation” and instead focused on identifying relevant grade-level content and scaffolding skills that students were to master. Within the guides, “we’ve embedded the essential learning, the essential vocabularies,” he says.

“It’s been a transition because we have typically focused on remediation in education, and that really hasn’t allowed us to move the needle on proficiency, or, by the same token, have the necessary gains we want students to have.”

PROMISING PRACTICES IN PLACE

When it comes to promoting learning, it’s crucial to recognize the value of students’ connections to teachers, school staff, and the school community, Patrick says. “What we know from the research is that students who have strong relationships with adults in school buildings are more willing to come to school and are more engaged. It’s important that we foster those strong developmental relationships.”

One of the special features of Guilford County Schools’ tutoring program is its collaboration with college students from nearby North Carolina A&T State University. The largest historically black university in the country, many of its students who major in science, mathematics, and engineering were among the first tutors tapped for the program. They “serve as role models for our students and our district, which is 75 percent Black and Brown,” Contreras says. “We know the research on the impact of having a teacher that looks like you, so we felt that having tutors who look like (many of our students) would have a very similar impact.”

PHOTO CREDIT: GUILFORD COUNTY SCHOOLS

As its tutoring initiative continues, Guilford County is taking a deep dive into what is the most effective use of the program and what really works. “We know we have promising practices in place,” says Whitney Oakley, chief academic officer. “We know that students have improved from failing grades to passing grades. We know that students are logging on for tutoring sessions or having face-to-face tutoring sessions more frequently once they have attended the first three sessions because they know they’re working.”

An external evaluation underway by researchers with the Annenberg Institute at Brown University hopes to shed important light on the program, including whether its two to six hours per week is the right tutoring dose, the right duration, or if some other amount is needed to get the desired outcomes. “That’s important to us, that we figure out if a student is three years behind in math, for example, at what point will you see improved outcomes,” Contreras says. “We’re really studying this closely.”

Michelle Healy (mhealy@nsba.org) is associate editor of American School Board Journal.

Share this content